A river reborn

A lawsuit settlement seeds the rebirth of a watershed and a community.

A lawsuit settlement seeds the rebirth of a watershed and a community.

Rick Orris

“A River Reborn” by Mangrove Media

“I never thought I’d be able to see this river fishable again.”

That’s Rick Orris, a retiree, talking about Pennsylvania’s Little Conemaugh River, once one of the nation’s most polluted waterways and the subject of the film “A River Reborn.”

The film tells a story of the rise and fall of Pennsylvania’s coal industry, the discharge of heavy metals that turned waterways orange, and a remarkable effort to bring a watershed back to life – made possible in part by a PennEnvironment lawsuit.

Coal dominated the Pennsylvania economy for more than a century. As oil and gas replaced coal in the 1900s, thousands of mines were left abandoned across the state. Minerals, air and water reacted to form sulfuric acid and iron. As rain fell over the years, the mines flooded, flushing out drainage that was rust-colored and as acidic as orange juice – eventually reaching the Conemaugh and dozens of other rivers, streams and creeks, killing most of the aquatic life in its path.

“By the time I was 10,” Rick Orris says in the film, “all the fish were gone. You could paint your car with the creek.”

David announces the GenOn settlement as NELC’s Josh Kratka (left) and Foundation for Pennsylvania Watershed’s John Dawes look on.

Matthew Limbach

A new opportunity

In 2007, our attorneys with the National Environmental Law Center (NELC) sued, on behalf of PennEnvironment, Sierra Club and individual citizen members from both groups, a company called GenOn Energy. The suit alleged the firm had been dumping illegal amounts of toxic pollutants—including selenium, manganese, aluminum, boron and iron— into the Conemaugh River. Four years later, on June 6, 2011, we announced that GenOn had agreed to end its illegal pollution and pay a $3.75 million penalty—the largest penalty of its kind in state history. That money provided the initial funding needed for new treatment plants to start cleaning up what the Foundation has called the “Super Seven”—the seven most-polluting abandoned mines in the Conemaugh watershed. The St. Michael plant, at the site of the largest abandoned mine, is up and running and pulling more than 99% of the iron out of the mine—an estimated 2.2 million pounds of it every year.

Branden Diehl and John St. Clair at the St. Michael treatment plant.

“A River Reborn” by Mangrove Media

Best of all, the watershed is cleaner. Rick Orris can go fishing again and even take his grandkids swimming. Chad Gontkovick started a tubing company that serves the river from downtown Johnstown. Jackie Ritko is leading kids on trips to study the river’s flora and fauna. People like Mike Cook take part in whitewater kayak and canoe events at Greenhouse Park. Melissa Komer, of the Johnstown Redevelopment Authority, marvels at the lively scene on weekends, with people traipsing around downtown wearing bathing suits before and after they head for the river.

“A River Reborn” by Mangrove Media

It’s a citizen action success story and, like all such stories, it’s one worth retelling. So we pitched one of our funders on putting the story on film. Ben Kalina, who also happens to be a PennEnvironment member, directed “A River Reborn.”

Since Ben finished the film, we’ve been doing our part to make sure people see it–resulting in more positive ripple effects.

A state representative attended an online showing we hosted with the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philly and she reached out to me to say how much the documentary moved and motivated her. We suggested she show “A River Reborn” to her colleagues on the state House Committee on Tourism and Recreational Development and join us on a tour of the river with the folks featured in the film. She pitched her Republican counterpart, who loved the idea. The committee set up a two-day tour this past April.

So I joined Ben Kalina, John Dawes (executive director of the Foundation for Pennsylvania’s Watersheds), and Mike, Chad, Jackie and Melissa from the movie, for a showing of the film in Johnstown, followed by a two-hour discussion. I then joined seven legislators (five Republicans and two Democrats), along with their staff and a few spouses, for a tour of the river, old steel mills that are being repurposed, and local parks that have been created with funds from Growing Greener (a state program the expansion of which was the goal of PennEnvironment’s first campaign back in 2002).

We’ll see where all of this takes us. But if there’s one thing that can bridge the partisan divide and help overcome political inertia, perhaps it’s seeing positive results with your own eyes.

“A River Reborn” by Mangrove Media

Topics

Authors

David Masur

Executive Director, PennEnvironment

Started on staff: 1994 B.A., University of Wisconsin-Madison As executive director, David spearheads the issue advocacy, civic engagement campaigns, and long-term organizational building for PennEnvironment. He also oversees PennPIRG and other organizations within The Public Interest Network that are engaged in social change across Pennsylvania. David’s areas of expertise include fracking, global warming, environmental enforcement and litigation, and clean energy and land use policy in Pennsylvania. David has served on the environmental transition teams for Gov. Tom Wolf and Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney. Under David’s leadership, PennEnvironment has won the two largest citizen suit penalties in Pennsylvania history against illegal polluters under the federal Clean Water Act and the largest citizen suit penalty under the federal Clean Air Act in state history.

Find Out More

A look back at what our unique network accomplished in 2023

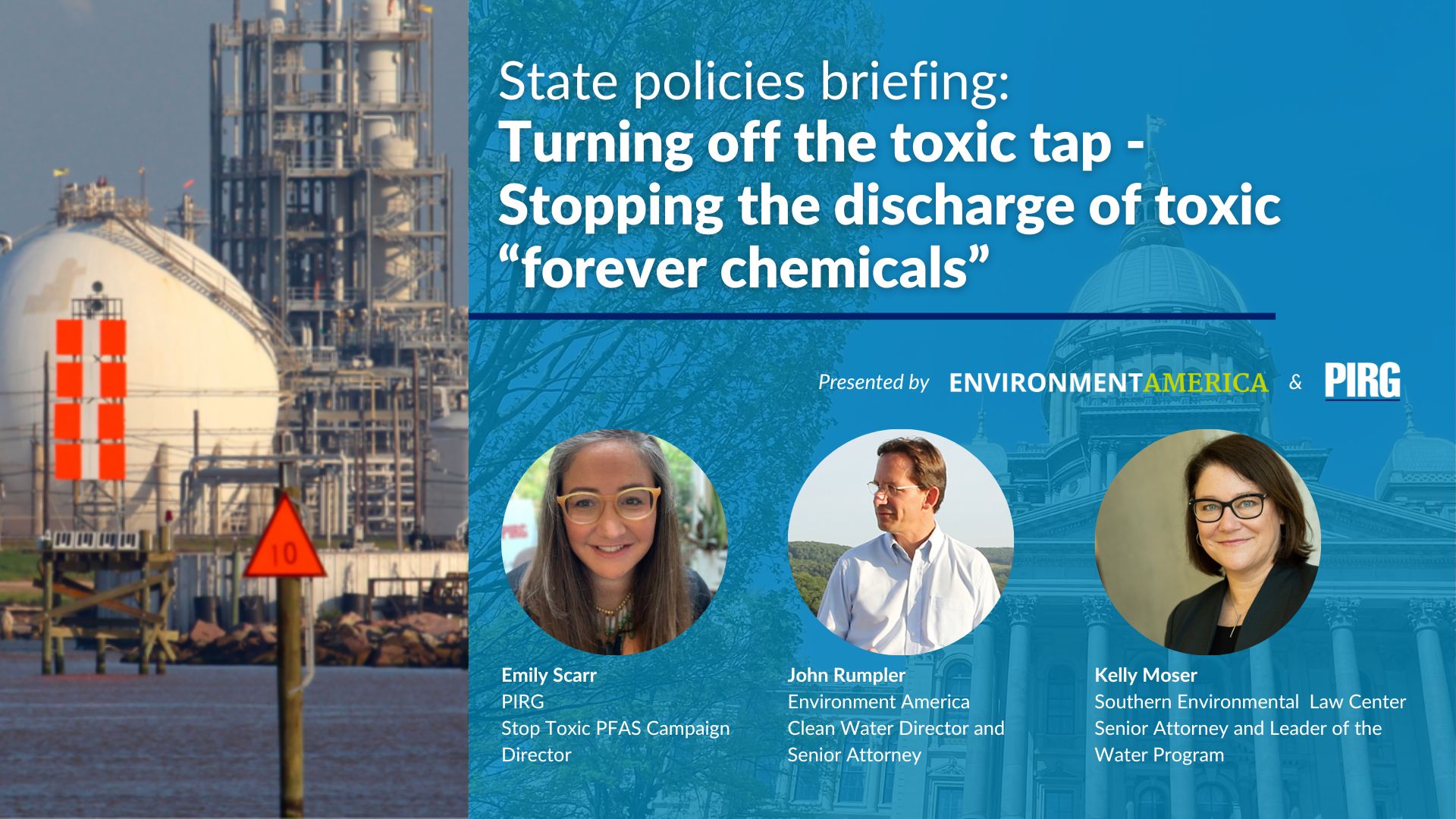

Event highlights role of states in stopping industries from dumping toxic PFAS

Got PFAS?